- Home

- Doyle, Paddy

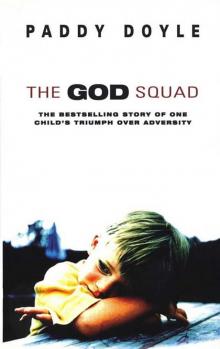

The God Squad

The God Squad Read online

THE GOD SQUAD

Paddy Doyle

CORGI BOOKS

Contens

Cover

Title

Copyright

Dedication

About the Author

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Epilogue

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781407084251

www.randomhouse.co.uk

THE GOD SQUAD

A CORGI BOOK : 0 552 13582 8

Originally published in Great Britain by The Raven Arts Press

PRINTING HISTORY

Raven Arts Press edition published 1988

Corgi edition published 1989

15 17 19 20 18 16

Copyright © Paddy Doyle 1988

The right of Paddy Doyle to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Set in 10.5/13pt Sabon by Phoenix Typesetting, Ilkley, West Yorkshire.

Corgi Books are published by Transworld Publishers, 61–63 Uxbridge Road, London W5 5SA, a division of The Random House Group Ltd, in Australia by Random House Australia (Pty) Ltd, 20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney, NSW 2061, Australia, in New Zealand by Random House New Zealand Ltd, 18 Poland Road, Glenfield, Auckland 10, New Zealand and in South Africa by Random House (Pty) Ltd, Endulini, 5a Jubilee Road, Parktown 2193, South Africa.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Cox & Wyman Ltd, Reading, Berkshire.

For Eileen

Paddy Doyle was born in Wexford in 1951 and now lives in Dublin. He is married with three grown up sons. He is recognized as a leading disability activist in Ireland and has been a member of the government-appointed Commission of the Status of People with Disabilities.

A frequent contributor to television, radio and the print media on matters as diverse as the role of the church in caring for children to the legalization of marijuana for medical use, he is currently Chief Executive of the National Representative Council – a body established to ensure that the rights of people with disabilities are upheld. He has also travelled extensively throughout Europe and the United States, speaking at conferences about disability and child sexual abuse.

Paddy Doyle was the first recipient of the Christy Brown Award for Literature, in 1984, for a television play entitled Why do I Bother. Shortly after it was first published, The God Squad became a bestselling book in both Ireland and the United Kingdom. It also won the Sunday Tribune Arts Award for Literature. In 1993 Paddy Doyle was awarded a Person of the Year Award for An Outstanding Contribution to Irish Society by the Rehab Group.

www.booksattransworld.co.uk

PROLOGUE

For years I had believed my uncle to be dead. Attempts at correspondence, spanning over twenty years and including an invitation to my wedding in 1974, had failed to bring any response. So that Sunday in 1983 as I drove with my family from Dublin my feelings were of trepidation. The phone call telling me he was still alive and in hospital in Wexford had come about because of the media exposure surrounding my being awarded the first Christy Brown Award for Literature.

How was he going to react to me – or I to him? I was aware of going to see a man who was ill, but even more aware that he was the sole living relative I had – apart from my younger sister. He surely would give me the information I needed about my parents and my past.

On arrival at the hospital, crowds were lining the grounds for the removal of the remains of a local dignitary of the church. I left my wife and children in the car and moved through them, overhearing their comments about my appearance on The Late Late Show the previous night.

I was nervous and waited outside the ward before asking a senior nurse to tell him I had arrived, explaining to her who I was and the number of years that had elapsed since he and I had last met.

As soon as I entered the ward we recognized each other and he began to cry. He was in some pain following the removal of his appendix and obviously distressed at seeing me. After awkwardly discussing his health, I asked him about my parents. At first he ignored my questions about them and would only reply repeatedly ‘You’ll be all right when I’m gone’. Finally I forced him to tell me that my mother had died of ‘the disease’ but he just wept when asked about my father, avoiding the question in every way he could. Eventually he revealed where my mother was buried but still consistently refused to say anything about my father. When I asked about photographs he said there were none.

Back in Dublin the suspicion of a conspiracy of silence which I had long held was reinforced and I was convinced that whatever happened to my parents had been deliberately concealed from me by the silence of a whole society and time. I knew so little that I even began to wonder if the man I called ‘uncle’ could in fact be my father. I discussed what had happened with a doctor friend and we decided that there had to be a way of getting to the truth. I was a man with no past. There must be someone who knew why I was sent to an Industrial School and somebody who could explain the origins or cause of my disability. Previous attempts at such ventures had failed. What past I did have amounted to a birth and baptismal certificate. Enquiries about medical records had yielded no results. I had no reason to believe that things would be any different this time.

Yet gradually the truth began to filter through as the thirty year conspiracy of silence slowly cracked. Unexpectedly I learned of the deaths of both parents in a letter from someone who did know of my past. Though the information was scant it was filling great gaps. I began to delve further and with the help and support of my wife, I intensified my search.

I discovered that on the morning of August 15th, 1955, I was taken to the District Court in County Wexford, where I was found to be in possession of a guardian who did not exercise proper guardianship. Two days after my appearance an Order of Detention in a Certified Industrial School was drawn up and brought to the house I was staying in by a Garda for legal execution. The form was signed by the Justice of the Court. I was four years and three months old at the time.

In early June of that year my mother had died from cancer of the breast and six weeks later my father committed suicide by hanging himself from an alder tree at the back of a barn on a farm where he worked as a labourer. I was taken into court by a woman who was later described as ‘a sort of an aunt’.

Earlier at the inquest into my father’s death, my mother’s brother who had lived with us had given a statement which I have in my possession. Part of it reads:

‘I left the house at 8.15 a.m. this morning 15/7/1955. When I was lea

ving Patrick Doyle was in bed. On my return to the house this evening at 9.15 p.m. Patrick Doyle was not in the house. I looked around the back of the house and later went to the haggard where I found him with a rope around his neck hanging from an alder tree on the fence. I felt one of his hands and it was cold. His feet were about two feet off the ground.

‘I didn’t cut down the body. I sent word to the village with a little girl that was passing for someone to come down to me. Someone arrived in about 15 minutes. A priest from the nearby parish cut down the body. Since the deceased man’s wife died about six weeks ago he has been worrying about her ever since. He was a labourer by occupation and about 52 years of age.’

A doctor had told the inquest that he had been called to the farm by the Gardai and after an examination had estimated that the time of death had been some twelve hours earlier. It appears that I witnessed the suicide and may have been found wandering on the farm in great distress.

It had taken me thirty years to discover the truth about the deaths of both my parents even though a death such as my father’s was likely to have made the local, if not the national newspapers, of the time. With that in mind I searched through old copies of The Wexford People in the National Library. There in the July 1955 edition I read the details of my father’s suicide, and the other events surrounding it. While searching through these papers I tried to find a death notice for my mother, but did not succeed. Reading a journalist’s report of the event made me realize that this was not a secret, unheard of event, but a public domain issue.

I began to pressurize my uncle for photographs, certain there must be some and that he could tell me where to look. A letter arrived at my home, containing a short note and two photographs: one of myself with a group of children on my First Communion day, the other of two women and a child in a buggy. The child was me, and the woman standing behind was my mother. Until then I had no idea what my mother looked like. Though she had obviously been a part of my early life, I had no memory of her. At 35 years of age I was seeing my mother for the first time. I didn’t cry, nor was I jolted in any way. Despite my best efforts I have as yet been unable to get a photograph of my father. I still have no idea of what he looked like, my only memories of him are those that haunted me as a child. A faceless man hanging dead. A fierce determination set in to get any information I could, which eventually resulted in my obtaining the original Order of Detention, rust marks from a paper clip etched on it, statements of witnesses given at the coroner’s court and other papers pertaining to his death.

There were many times during the course of writing this book, that I questioned what I was doing, often frightened by the chill running through my body as I wrote. The support I received from people, particularly Eileen, my wife, was limitless. The impact of having to absorb one shock after another was at times very painful for her and she cried enough for both of us.

Many people familiar with the effects of institutional care, particularly Industrial Schools, will say that I have gone too easy on them. Lives have been ruined by the tyrannical rule and lack of love in such places. People have been scarred for life. Others will wonder why I bothered to delve into the past at all.

This book spans just six years of my life. There was almost consistent trauma, ranging from the death of both my parents, to the isolation of hospital wards and brain surgery. Such surgery was not just traumatic, but debilitating also. One procedure could not be completed because of the breakdown of the apparatus, prompting me to wonder why it was not attempted again when the apparatus was repaired.

It is important to point out that interspersed with this trauma were moments of great love and affection. From the gentle kiss of a young nurse to the soft hand of a caring nun. It may well be the case that these were the moments which preserved my sanity and gave me something to live for.

This book is not an attempt to point the finger, to blame, or even to criticize any individual or group of people. Neither is it intended to make a judgement on what happened to me. It is about a society’s abdication of responsibility to a child. The fact that I was that child, and that the book is about my life is largely irrelevant. The probability is that there were, and still are, thousands of ‘mes’.

Paddy Doyle,

Dublin,

Sept. 1988.

CHAPTER ONE

I lay flat on my back on the narrow cast iron bed in the dormitory of St Michael’s Industrial School in Cappoquin. The thin horse-hair mattress was barely adequate to separate my thin body from its taut criss-cross wire springs. My eyes were fixed on the ceiling, the paint flaking just above the bed. From a room below the sound of children singing seeped through the floorboards.

In the distance a train hooted, heralding its imminent arrival at the station just beyond the high granite walls of the school. I turned towards the tall sashed window a few feet from my bed. Through watery eyes I noticed the sun was shining, though the dormitory was cold and dark. The train hooted again, louder as it drew nearer the station, panting and hissing through the stillness of the day.

It had been three weeks since my uncle had driven me here in the black Morris Minor owned by his employer. In his pocket he carried the order of detention from the District Court in Wexford sentencing me to seven years in custody. The charge against me was of being found having a guardian who did not exercise proper guardianship. I was then four years and three months old. I remember being terrified of the nuns from the moment I entered the Industrial School and clinging to my uncle, pleading with him to take me home. A tall, thin evil-looking nun had come towards me and forced my hand away from his before gripping my jumper at the neck to ensure that I could not grab hold of him again. I’d screamed and kicked in an attempt to free myself, but the more I struggled, the tighter her hold became. She told my uncle that I would settle down just as soon as he left. I can remember trying to get free of her and follow my uncle. But the nun held me firmly by the ear lobe and warned me to stop, otherwise I would receive a ‘good flaking’.

Three weeks had taught me the meaning of that phrase. I rose cautiously from my bed, rubbed my eyes and cheeks with my knuckles and went towards the window. I stood back, frightened that I might be seen from the yard below. I moved as close to it as I felt it was safe to do.

The granite wall glistened in the sunlight like a million jewels. I pressed my face against the window and watched the approaching train. The sun shone onto its black rounded front like a spotlight. The shiny, black funnel belched out a mixture of smoke and steam that hung above the tender in a large plume of grey and white, and when the colours merged to black and soared into the sky the cloud cast a dark shadow across the grey concrete of the school yard. Behind the glossy tender, the wagons laden with sugar beet rattled along, zig-zagging awkwardly in contrast to the graceful, steady movement of the engine. A screeching of the wheels on the tracks and a loud prolonged hissing brought the engine to a halt. I noticed the sparks made by the wheels as they skidded along, igniting in the dark shadow of the underframe. A final banging of the wagons as each one buffeted into the one ahead of it, then silence. Total silence. Two men in blackened boiler suits jumped cautiously from the tender and stood briefly in the hot sunshine as both rubbed their foreheads with a sleeve. Before leaving the train each in turn slapped the great tender on its belly as a farmer would a cow, or a jockey a horse, a sign of affection, the beast had done her job well.

I counted the wagons as the tender took water from the great red-oxide tank overhead. There were fifteen, and a guard’s van at the rear. Each one filled with sugar beet, mud baked by the combination of hot sun and drying breeze. The stillness of the moment was broken by a sudden rush of feet into the yard below the dormitory window. I backed away from the window though I still looked out as the other children ran about the yard screaming their excitement. Some of them tried to climb the wall to get a better view but their efforts were brought to an abrupt halt by the swish of a cane from one of the nuns patrolling the yard like a black sh

adow. One boy who was midway up the wall fell to the ground writhing in pain having felt the full force of Mother Paul’s cane across his calf muscles. He lay curled up, on the ground screaming and gripping his leg tightly. The other boys stood still, frozen in terror.

I watched. I knew the pain of the bamboo and the horror of being beaten until it was no longer possible to stand it. As blow after blow landed, I trembled, fully convinced that I would receive similar punishment when Mother Paul came to the dormitory. I went back to bed and pulled the covers over my head in an attempt to escape the piercing, painful screams. Finally the screaming stopped. I lay waiting for the footsteps.

‘Well, Master Doyle . . . are you finished now or would you prefer to spend more time here on your own?’

Startled by the sound of Mother Paul’s voice, I turned down the bedcovers. Her tall black-clad figure stood beside my bed, her wrinkled hand carrying the cane that she kept partially hidden up the long loose sleeve of her habit. She stared coldly down at me, her icy-blue eyes seeming magnified through the thick lenses of her rimless spectacles. Her long pointed nose threatened to drip its watery contents onto my bed but was halted by the swift use of her check-coloured handkerchief. Her wicked-looking face was gripped tightly in the habit of the Sisters of Mercy. The black habit was pulled tight at the waist by a leather belt.

‘Get up out of that bed then this instant,’ she roared, ‘and I don’t want to hear another word from you about a man hanging from a tree. It’s not good for the other children and, besides, people don’t do that sort of thing.’

‘But there was . . .’

The nun’s mouth tensed visibly. ‘That is enough, I warn you. Get dressed and get down to the assembly hall immediately.’

The God Squad

The God Squad